While travelling in South East Asia, we stayed on many small islands. Koh Phangan, Koh Chang, Koh Rong Sanloem, Gili Air and most recently on Camiguin.

I love islands. The 360 degree surroundings of the sea give an ultimate exotic feeling. I am not the only one. Islands and coastal areas in South East Asia are popular and with the rise of tourism, the paradise areas have slowly turned into densely populated spots. Sometimes, the surrounding sea is also full of colourful fish and bustling with corals, a true magnet for tourists and a precious natural resource.

However, corals and their habitat are fragile. Not only do they break if carelessly touched or stepped on, they are also sensitive to the chemical composition of the water.

Poor in nutrients, rich in diversity.

Clear water, the one great for snorkelling and diving, is poor in nutrients and organics. Complex communities like corals grow slowly, and therefore develop into diverse communities that co-operate to share the few resources available.

When water gets richer in nutrients and organics, the fast growers, algae and bacteria, get an edge and overtake the slow growers. Water ceases to be clear, instead it becomes green/brown tinted. As oxygen concentrations drop, corals die and fish leave – dead zones are created.

Tourism and wastewater.

As tourists come flooding the favourite spots, numerous restaurants and resorts start popping up on the coast. The closer to the beach, the more attractive they are. There are laws preventing building too close to the coast, but under the rule of a corrupt government, an exception to the law can be bought. Thus concrete replaces sand and luxury resorts and hotels begin to fill the coast. Air conditioning, majestic view, swimming pool and, although unseen, huge septic tanks to collect the guests’ waste.

Septic tanks are containers located under the ground, and in some places they collect water only from the toilets, and in other places also from the showers and washrooms. The solids settle and are anaerobically decomposed into fatty acids and methane. As soon as they fill up, more incoming water will trickle out of the tank into the surrounding soil or sand.

Sewage pollution is shockingly widespread: A full 96 percent of places that have both people and coral reefs have a sewage pollution problem, according to recent research by Stephanie Wear, The Nature Conservancy’s lead scientist for coral reef conservation. (Source: nature.org)

Thinking of sleeping near the beach? Think twice. Wastewater is rich in nutrients (P, N and C). And tourists produce a lot of wastewater which trickles straight into the sea. Especially if the septic is near the shore and at low tides. The wastewater you have produced is lethal to the sea life which you came to observe here. The crystal-clear water, so inviting to dive into, will fade and turn into an algal-bacterial soup.

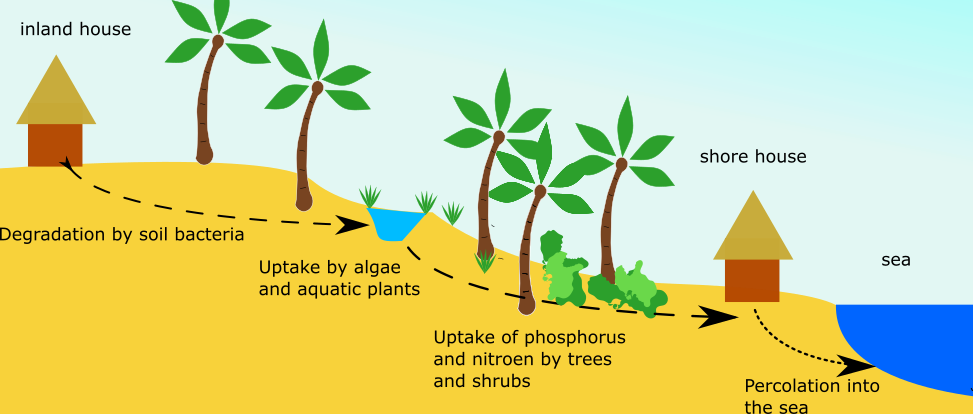

In case you stay further away from the beach, wastewater will slowly percolate through the soil and sandy bed. Soil hosts plants and bacteria that can take up, absorb or degrade nutrients further, so they don’t reach the sea water. In case you’re located on the beach, no such degradation has time to occur and all percolates straight into the water.

Case study- Gili Air, Lombok, Indonesia.

On Gili Air we stayed in a bungalow about 500m from the beach. The area is quieter than the port and the room price also a tad lower. Our host described to us his concern about building on the coast and his frustration about the corrupt officials. Currently, many bungalows and resorts are growing on the east coast, well within the “forbidden zone”- 50 m away from the high tide line, to accommodate more visitors. Although many inhabitants of Gili are aware of the “wastewater problem”, the vision of fast cash from built up hotels is too tempting.

The island offers the last little area of coral reef accessible to snorkelling on the east side, near the port. The coral provides a shelter to many colourful fish. Hundreds of tourists (who feed the fish, which is also bad) pass here every day to watch the spectacle. Some coral is still alive, but the majority is bleached and dying. Much of it is turning green, being overgrown by algae. If the coral is completely gone, flocks of fish will go too. The island’s last patch of natural resource will cease to exist.

When the snorkelling opportunities are gone, the island will either turn into another “party spot”, offering nothing more than bars and clubs, or tourists will stop coming altogether and hotels will remain empty.

How to stop it?

So before it’s too late, let us do a few things. Let’s implement better decentralised waste water treatment systems, like explained in the previous blog, and before that happens, let’s try not to go to big hotels too close to the beach and let’s not feed fish when visiting corals.

A lot must be done to keep the corals alive and treating waste water responsibly is certainly one of them. Placing wastewater into the equation of ecotourism should be the next step. The coral ecosystems are suffering not just in Indonesia, Thailand is a great example too.

Every place hit by tourism is affected to some degree and with tourism on the increase, the trend is not sustainable, so let’s change it soon!